If you don’t have $20 million, relax. A wealth tax won’t hurt you. »

By Linda McQuaig, reproduced from the Toronto Star, April 13, 2021.

Benjamin Franklin observed that nothing is certain except death and taxes.

Another certainty is that the wealthy will concoct fatuous arguments to justify lower taxes for themselves.

The ultra-rich have been so relentless in making their case — or having hired guns make it for them — that they’ve managed to largely shed their tax burden in recent years even as they’ve grown spectacularly, exorbitantly, astronomically wealthy. (Canada’s wealthiest 87 families had wealth of $259 billion in 2016; our top 44 billionaires increased their wealth by more than $50 billion during the pandemic.)

Most Canadians have had enough of this. A recent Abacus poll shows that a striking 79 per cent of Canadians favour a wealth tax.

In fact, a wealth tax would be the simplest, fairest and most effective way to collect billions of extra dollars of revenue a year, and to limit the power and political influence of the billionaire class.

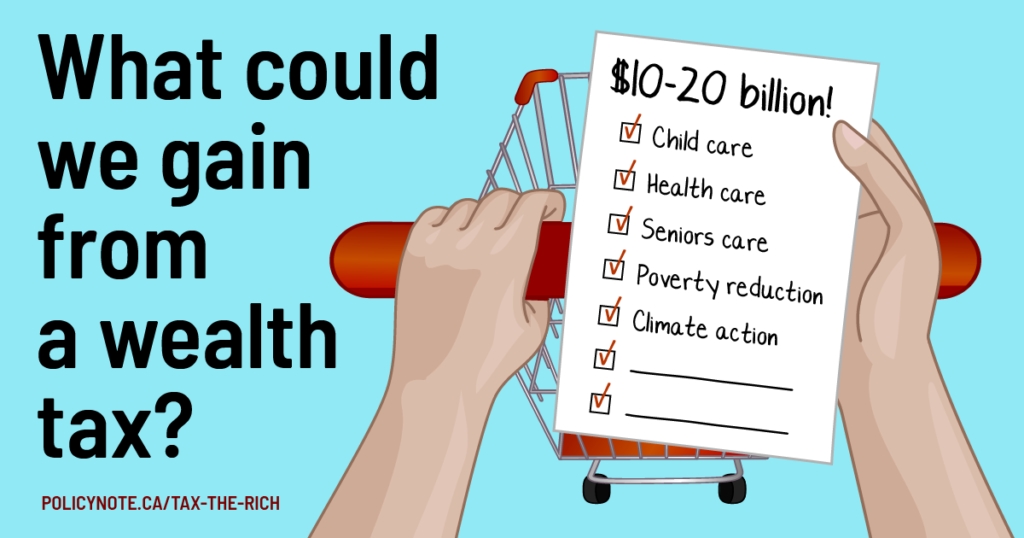

A wealth tax only targets the wealthy. An NDP proposal — based roughly on proposals by U.S. senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — would levy an annual tax of 1 per cent on net wealth above $20 million. If you don’t have $20 million, it’s not coming for you.

The NDP plan would raise an estimated $10 billion a year — or more if the rate rose for bigger fortunes, notes economist Alex Hemingway of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Here are some of the facile arguments being trotted out against a wealth tax.

A wealth tax is foreign to the Canadian tax system. In fact, Canada already has such a tax. It’s called the property tax. It’s imposed on almost all the wealth held by low and middle income Canadians — their homes. A wealth tax would simply extend the property tax to include other forms of property mostly held by the wealthy, such as stocks and bonds (above $20 million).

A wealth tax has not worked in other countries. The wealth taxes adopted in many European countries were badly designed. They had low thresholds, so they taxed many people who were not ultra-rich, just well-off. Today’s proposed wealth taxes only target those who are clearly, undeniably wealthy.

The ultra-rich will find ways to evade or avoid the tax. Our tax laws, which permit widespread tax avoidance and evasion, are not laws of nature but policy choices made by legislators. Stopping tax evasion is simply a matter of political choice — especially with today’s technology that makes it easy to digitally trace the movement of money. An increase in Revenue Canada’s enforcement budget — to be used against tax haven trickery — and tougher penalties for cheaters could be extremely effective. The only thing lacking is political will.

A wealth tax would discourage savings and entrepreneurship. Hardly. The tax would only hit those who have accumulated enormous assets, typically long after their initial entrepreneurial effort (or those who have inherited huge assets through no effort). Does anyone seriously believe that, in the future, creative Canadians would stop being entrepreneurial if they thought they would only end up with a fortune of, say, many hundreds of millions of dollars rather than perhaps a billion dollars?

Some wealthy taxpayers have very low incomes and thus might not have the cash to pay an annual wealth tax. If truly wealthy individuals have small incomes it’s because they’ve arranged their finances this way in order to avoid paying income taxes. They could easily sell some of their assets. There’s no reason to sympathize with their plight. After all, if working people lose their jobs, they’re forced to sell assets (except their homes) until they’re sufficiently poor to qualify for welfare benefits.

A wealthy family could lose control of a family business if it were obliged to sell shares in order to pay the wealth tax. Highly unlikely, but possible. But so what? There’s no evidence that wider corporate ownership would be a bad thing.

Bill Sundhu

Bill Sundhu is a Canadian lawyer and former judge with more than 35 years of experience in the courts of justice.

His current practice includes trial and appellate advocacy in criminal justice, human rights and civil liberties. Bill has broad legal experience that includes criminal justice, family law, child and youth law, indigenous rights, police misconduct and wrongful deaths, non-discrimination, access to justice, law reform and legislation, professional legal responsibility, and judicial independence and administration.

He is a regular speaker, lecturer and media commentator on human rights, justice, diversity, equality and international legal issues. He has extensive knowledge of the Canadian justice system and international human rights law, with particular interest in international criminal law.

Bill has three university degrees, including a Masters degree in International Human Rights Law from Oxford University. He practices in Canadian and International Law.

His work is recognized by appointment to the List of Counsel for the International Criminal Court in the Hague (war crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity) and selection to a panel of international experts to train judges in Tunisia, in 2013-14 in human rights and administration of justice. He has served an extensive term as an Executive Member of the Canadian Bar Association National Criminal Law Subsection.

Bill is a founding member of the BC Association of Multicultural Societies and is an advocate for equality and diversity. He and his family have made Kamloops, British Columbia, their home for the past 24 years.

My Blog Posts Visit My Website